One year after Obama’s election in November 2009, I travelled America searching for answers to major historical questions about slavery involving many places and people across the globe. It troubles me that two of the first three American presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, kept slaves. They also fully utilised the income their tobacco plantations brought them in their roles as revered patriots and freedom fighters in the new America – ultimately leading to freedom for the slaves. To someone like me who has the blood of African heritage running proudly through my veins, yet knows that my ancestors chopped sugar cane in the heat of the South American sun in Guyana, the issues of freedom and slavery are as contrasting as the difference between light and darkness.

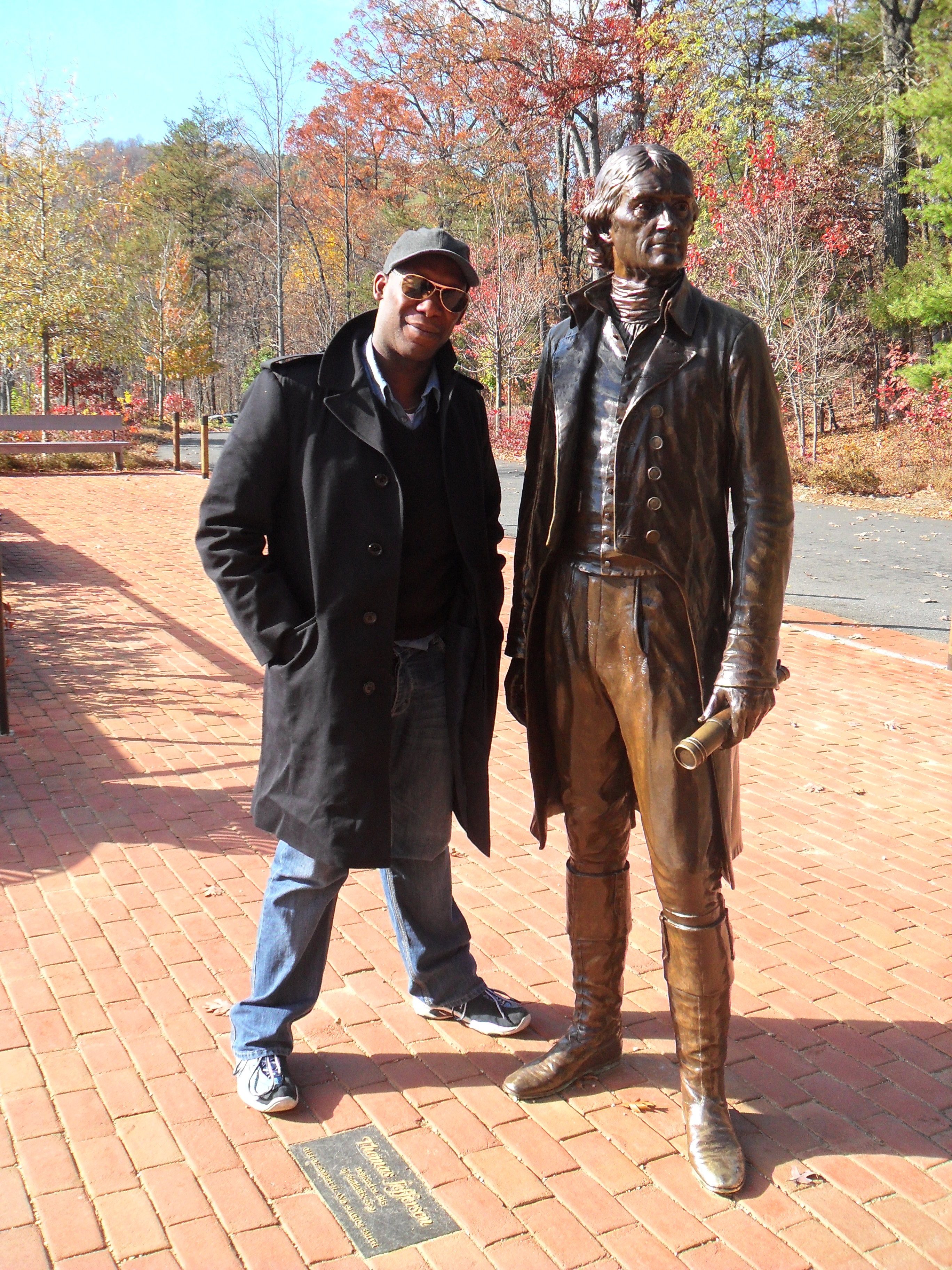

My search for some answers to these historical puzzles began at President Jefferson’s plantation Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Monticello is the president’s former home, built on a mountaintop with a panoramic vista across Virginia and the nearby university town of which Jefferson was a patron, Charlottesville. His sumptuous twenty-one-room, three-storey neoclassical mansion house – which President Jefferson designed, and which is replicated in his monument on the Washington Mall – dominates the thousands of acres that encompass it. The plantation is a network of gardens, buildings and farms that grew a variety of crops and housed animals tended by over 200 slaves. There is plenty of evidence that Jefferson was a benevolent owner. In keeping with the thinking of the day, he viewed slaves as we would children: unable to live independent lives of their own. As I walked among some of the slaves’ quarters – built below ground so as not to spoil the stunning views – I could begin to piece together how such a system existed and flourished.

Plantation owners ruled over millions of lives from the cradle to the grave, and sustained the growth of the transatlantic slave trade. Though British colonial slavery was first used in Virginia, the ‘peculiar institution of slavery’, as it became known, was assisted by British settlers from Bristol, who brought their African slaves with them from the British colony of Barbados into the then royal colony of South Carolina. Through Charleston, South Carolina’s major slave trading port named after King Charles II, a large-scale importation of African slaves arrived and successfully began to cultivate rice on its plantations. Slavery spread to Georgia and throughout the southern states of America, establishing the power and grandiose ways of the plantocracy.

Slavery became entrenched into the southern way of life, which it would take bloodshed and civil war to bring to an end. Tracing the links between the Piedmont tobacco plantations and the newly formed southern plantocracy, I found both spiritual and emotional connections between my home in Bristol, my parents’ origins in the West Indies, their family’s migration to America, and our shared heritage from West Africa. Like many before me, I began to connect my own past on a vast continental scale via the transatlantic slave trade, from Africa to the Americas, and through to the role of the Europeans.